In this post, we’re going to explore the Open Source project known as Dapr (The Distributed Application Runtime). This post is primarily aimed at those who already have an understanding of Containers, Kubernetes and Microservices. However, if you’re not familiar with these topics - I’ll do my best to set the right context and background without making the blog too lengthy!

Contents

In this post, we’re going to explore the Open Source project known as Dapr (The Distributed Application Runtime). This post is primarily aimed at those who already have an understanding of Containers, Kubernetes and Microservices. However, if you’re not familiar with these topics - I’ll do my best to set the right context and background without making the blog too lengthy!

Are you building a Microservice based system? Are you looking help to solve frequent challenges that come with this architecture? Challenges such as encryption, message broker integration, observability, service discovery and secret management are frequent in this archetype. This is exactly where Dapr shines, and may be of value. If this sounds like you, then carry on reading to find out more!

But first, What is a microservice?

There is a common misconception that to build a microservice based architecture that you have to build with containers. That is absolutely untrue. I could build this type of architecture using Azure App Services, Virtual Machine Scalesets, Azure Container Apps or Containers in an Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) cluster. Likewise, I could build a monolith by using any of those technologies as well.

Some of those underpinning cloud services may be a more natural fit to the microservice or monolithic architectural pattern. But in a nutshell, microservices does not equal containers.

Instead, a microservice architecture is a collection of services which are loosely coupled, easily maintainable and independently deployable (compared to a monolith, which is typically the opposite of those characteristics!).

Why Dapr?

Back in 2019, Microsoft announced Dapr to the world. With the continued growth of cloud and increase in cloud native applications being built, the adoption of microservices grew in parallel.

This is unsurprising. Microservices offer some great benefits, including -

- Separation of concerns which can lead to simpler maintenance compared to a monolith

- Reduced deployment times, and more efficient operations (i.e. DevOps improvements)

- A lower ‘blast radius’ if there is a problem during the deployment of a given service, due to independent services

- Empowerment to use different languages, frameworks and technologies per microservice

- Empowerment for separate teams to own their individual services in a distributed manner

- Ability to scale each microservice independently

- Loosely coupled microservices, which - if designed with appropriate patterns - could lead to a more resilient architecture.

- If you want to find out about some of the Cloud Design Patterns, check out my series on Architecting for the Cloud, One Pattern at a Time

“Well, those sound like some great benefits. Let’s get using Microservices right away!” is what quite a lot of engineering teams, developers and others have exclaimed. While these benefits are all completely true and valid, microservices bring along their own challenges.

- If you decide to use different languages, frameworks and technologies per microservice, you may have to create the same ’enabling logic’ (e.g. retry, circuit breaker, etc.) in different implementations

- It can be challenging to build a true microservices system, compared to a ‘distributed monolith’

- The level of automation and operational needed to manage a microservice environment increases proportionally to the number of microservices deployed

- In addition, consider the architectural complexity of managing any dependencies and relationships between all of those services

- Building an end-to-end view of a user journey through your system can be hard. e.g. If I purchase something from your store, I may interact with 5 different microservices as part of that transaction. If there is a failure, how do you know where the failure is, why it happened and what action needs to be taken? Who is responsible for the fix? Especially if different teams own the different services?

- Each microservice will have its own lifecycle, and potentially a separate team owning it. How do you easily and consistently test cross-service calls, without breaking the dependencies of other microservices?

- What is a microservice? When is a microservice too small, or too big?

- Domain Driven Design could be a blog post in its own right, so we’ll be avoiding that rabbit hole here!

Like any technical problem, we need to weigh the strengths against the weaknesses, the pros against the cons, the opportunities against the risks. The common theme of agility and independent scalability with Microservices, is a particularly attractive proposition in a cloud environment, allowing us to optimise for cost while meeting business objectives.

This is where Dapr fits in. Dapr aims to solve several of the challenges that I noted above. The aim is to allow developers to focus on their core application / business logic, and worry less about solving the challenges of building a distributed system.

How does Dapr work?

The sidecar concept

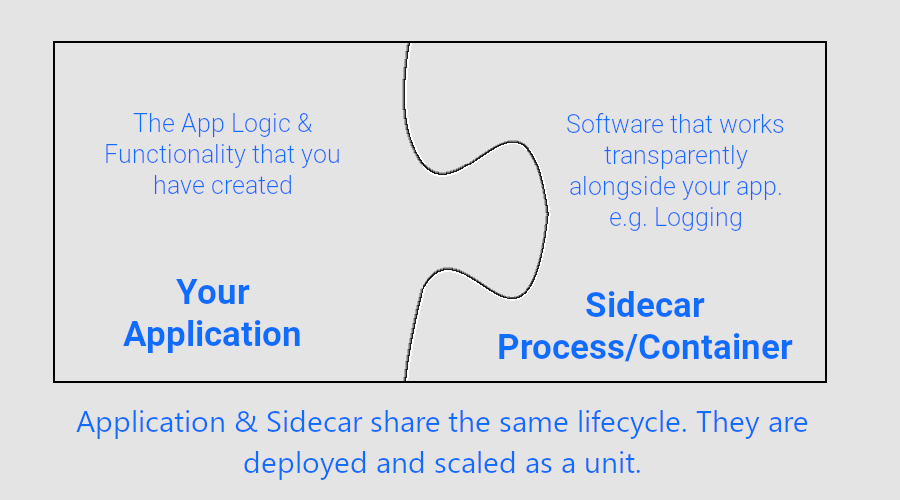

Conceptually, Dapr works by using the sidecar pattern. A sidecar is a secondary piece of software that is deployed alongside the primary application, typically in a separate process.

In a Kubernetes environment - this could be achieved by deploying two containers (the primary application container, and the sidecar container, e.g. an agent which intercepts network calls) in a single pod. The application and the sidecar typically share the same lifecycle, so would scale out/in together as well. The idea is that the sidecar’s software works transparently alongside the application, providing supporting functionality to it.

If you prefer analogies, consider a motorbike with a sidecar (this is where the term comes from!). The sidecar does not ride on its own, but enhances the motorbike (e.g. increases the capacity of the motorbike).

The Azure Architecture Center has a great writeup on the sidecar pattern.

When using Dapr, you deploy a Dapr sidecar alongside your application. This is what gives you several of the benefits that we’ll see a little later on.

You can find out further details on the Dapr sidecar architecture here.

Getting started locally

To get started with Dapr in a local environment, you’ll need to use the Dapr Command-Line Interface (CLI).

You can download the CLI in several ways, all of which are well documented on the Dapr Docs for Linux, macOS and Windows.

Dapr can be configured to run in a self-hosted mode, deployed in Kubernetes, or onto a serverless solution such as Azure Container Apps. The preferred self-hosted option depends on Docker Containers, but can run without Docker.

Note: The recommended developer environment is to use Docker.

Make sure you have installed the Dapr CLI and installed any needed dependencies for your preferred hosting method before progressing.

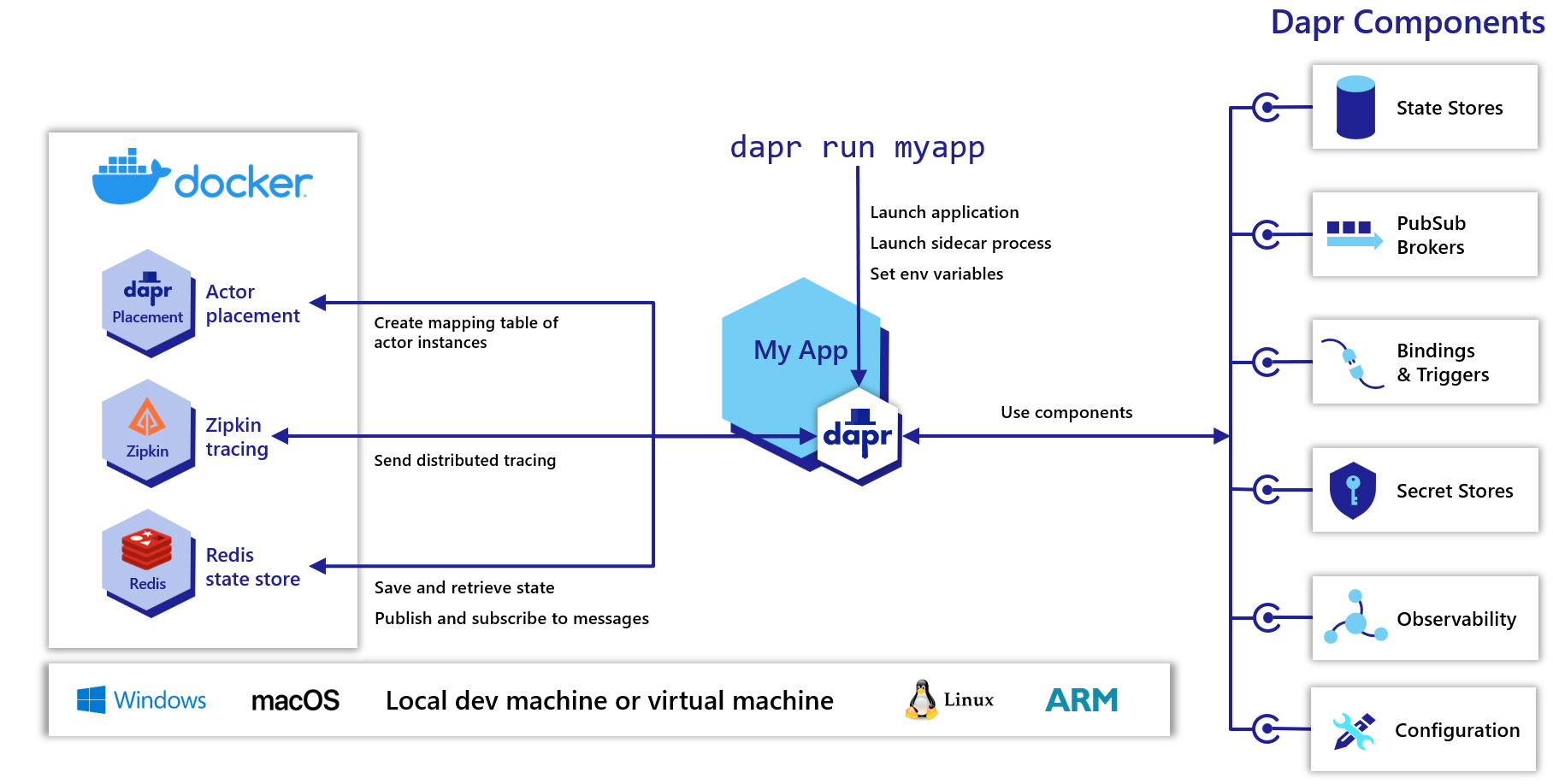

Self-hosted Dapr with Docker

The first step is running the dapr init command. This initializes your Dapr environment.

It will create the Dapr control plane in your local environment. In the docker hosting method, it will also create the following components -

- A docker container running an instance of Redis. The purpose is to have a default component for state management and pub/sub.

- We’ll cover the concept of components a bit later.

- A docker container running an instance of Zipkin. Zipkin is a separate OSS project which aims to solve the problem of distributed tracing (more information available on their site). Dapr uses this this for diagnostics and tracing across the deployed apps (microservices).

- Several Dapr configurations and components are installed in a .dapr directory on the local machine. The exact location depends on the Operating System that you’re using.

- An additional service

dapr-placementis created only if your application uses the Actor framework.- If there’s interest, please let me know! I can write up a separate blog post on the Actors framework and how to implement in Dapr.

A more detailed explanation of this hosting method can be found on the Dapr docs - How-To: Run Dapr in self-hosted mode with Docker.

Self-hosted Dapr without Docker

As a reminder, the recommended Dapr developer environment uses Docker. However, there may be scenarios where this is not an option for you. If you want to initialise without docker, then dapr init --slim is the command that you’re looking for.

There are some slight differences in what you get as a result of this command -

- Two binaries are installed; daprd (i.e. the Dapr sidecar executable), and placement (only required when using the actor framework, for placing actors across different partitions).

- The default components such as Redis and Zipkin are not installed in the slim mode. This means that if you want any Pub/Sub, State Store, Bindings or Secrets Components, then you would need to first establish a way of running the underlying service (e.g. install Redis locally, or use some hosted version), and configure the appropriate Component definition file (more on that later).

- Note that service invocation will be available out of the box, with thanks to the Dapr sidecar executable.

A more detailed explanation of this hosting method can be found on the Dapr docs - How-To: Run Dapr in self-hosted mode without Docker.

Running your application locally

Once you have the CLI setup and initialised Dapr on your local machine, you can begin to execute Dapr alongside your application! The deployment steps will differ when you’re deploying it into a live environment, such as Dev, QA or Prod (Dapr is typically hosted in Kubernetes in these types of environments, but more on that later).

As usual, it would be recommended to have a separate non-production environment to test your deployment procedures ahead of a production rollout.

To run the Dapr sidecar and your application side-by-side, you’ll need to use the dapr run command. The CLI has a full reference available here.

It boils down to a few key aspects (dapr run [flags] [command]).

flagsare clearly documented on the reference page noted earlier.Commandis the CLI input that you would use to execute your application.- In Node.js it could be something like

dapr run --app-id MyNodeApp node app.js - In .NET Core it could be something like

dapr run --app-id MyDotnetApp dotnet run

- In Node.js it could be something like

At this point, we should be able to have the Dapr sidecar running alongside our application. A lot of the value with Dapr comes from the abstraction of the components that we’d interact with (e.g. State Stores, Secret Stores, Bindings, Configurations, Pub Sub providers, etc.).

We haven’t configured those, or told our application how to interact with them. Let’s take a look at those next.

Dapr Building Blocks and Components

Dapr provides several modular building blocks that provide the common best practices for building microservices. These building blocks are exposed over HTTP or gRPC.

There are several building block types, including -

- Actors - Actors are a way of managing state across multiple partitions as reusable objects.

- Bindings (Input/Output) - Build event-driven applications based on the pluggable and modular Dapr component interface.

- Configuration - Used to easily share application configuration changes, and provide notifications of configuration changes.

- Observability - Used for diagnostics and tracing across the components and applications deployed with a Dapr sidecar.

- Publish and Subscribe - Ability to decouple components by using Pub/Sub brokers between services.

- Secret stores - Used to securely store secrets in a secure way (i.e. not plain text!), and allow your application to access those securely.

- Service-to-service invocation - Used in combination with the service invocation capabilities of Dapr. This may vary depending on the underlying hosting option (e.g. self-hosted, Kubernetes or a cluster of machines).

- State management - Enables you to create services that can persist state.

These building blocks (consider them like interfaces) are implemented as components. These components are pluggable, so you could easily switch these out with different implementations. For example, switching a messaging broker dependency from Azure Storage Queues, Azure Service Bus Queues, Amazon SQS, Apache Kafka, etc. by changing the configuration file for the component. The building blocks may use a combination of components (e.g. both Actors and State Management use state components).

What are Dapr components?

The Dapr docs describe components as Modular types of functionality that are used either individually or with a collection of other components, by a Dapr building block.

Effectively, they are a way to take the ‘common denominator’ approach to building your dependencies as building blocks. Your application shouldn’t need to worry or care whether it’s talking to a specific type of queue. It talks to a Pub/Sub component, and Dapr (as well as your Dapr configuration) deals with the rest.

- Bindings (Input/Output) - Build event-driven applications based on the pluggable and modular Dapr component interface. Each binding’s properties will be different, based upon the underlying service (e.g. AWS S3, Azure Storage Queues, Cron etc.)

- Configuration - Used for persisting application state, to easily share application configuration changes or for startup.

- Middleware - Plug in custom middleware into the HTTP pipeline, such as authentication or message transformation.

- Name resolution - Used in combination with the service invocation capabilities of Dapr. This may vary depending on the underlying hosting option (e.g. self-hosted, Kubernetes or a cluster of machines).

- Pub/sub brokers - Ability to pass messages to/from pub/sub providers such as Apache Kafka, Azure Service Bus or GCP Pub/Sub.

- Secret stores - As you would expect, a secret store is used to offload secrets into a trusted environment, so that you don’t need to reference them in plain text. Consider services such as Hashicorp Vault, Azure KeyVault, AWS Secrets Manager, etc.

- State stores - Applications these days typically hold and interact with some form of state (e.g. records applications, inventory, etc.). The state store gives us a pluggable way of interacting with data stores such as databases, files, memory caches, etc.

You can find a list to each of the component specs in the Dapr components reference documentation.

The components are created by the community. If you’re interested in contributing, you can do so on the dapr/components-contrib GitHub repository.

To avoid this post becoming too long, we’ll create an end-to-end example in a separate post. I’ll update this post with a link to it when available!

Running Dapr in a remote environment

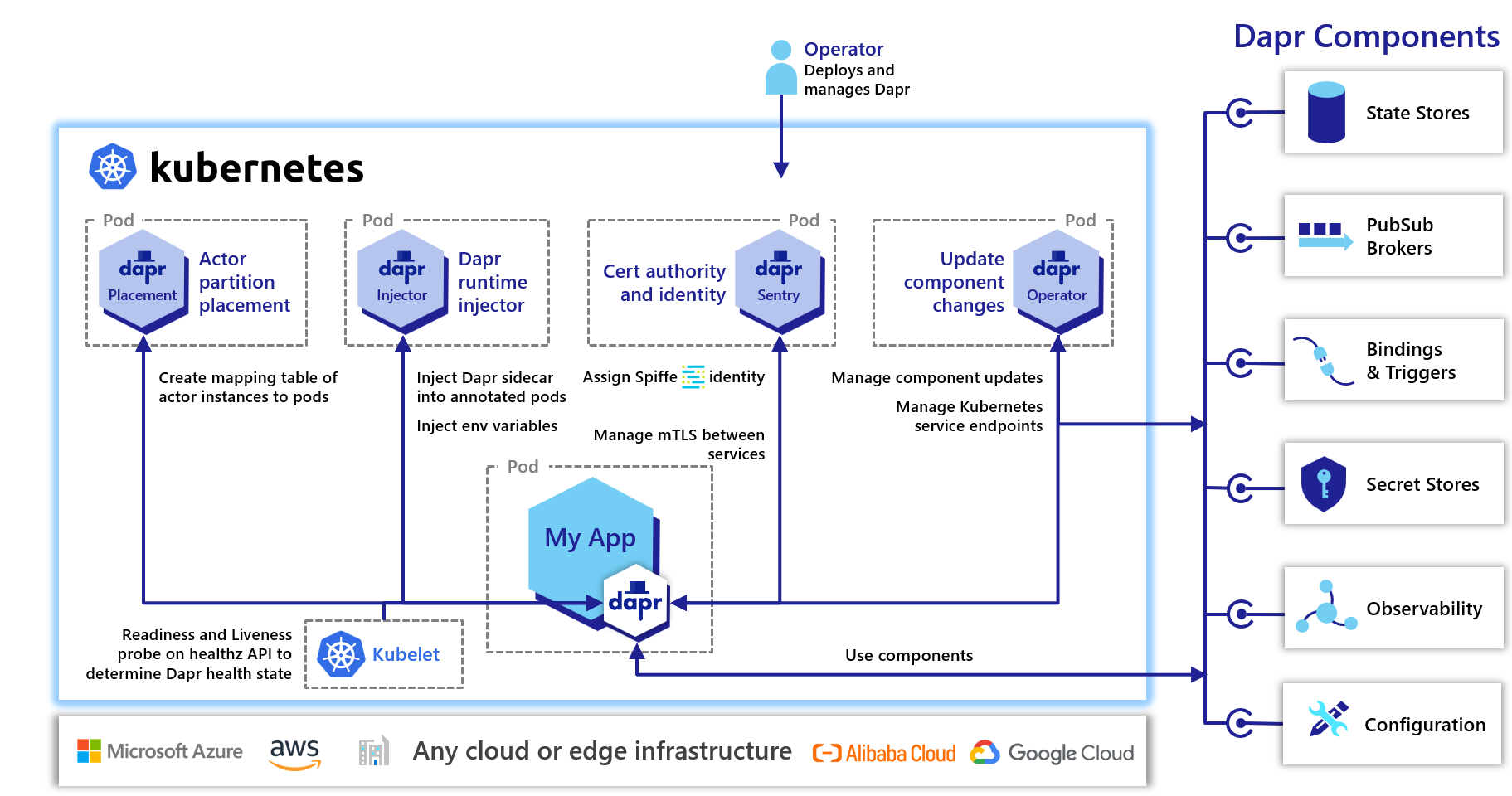

You’re most probably targeting a Kubernetes environment for your remote Dapr deployment.

The initialisation process using the Dapr CLI is very similar to the local version. Rather than just using dapr init, you’ll need to append the -k flag.

Important: Before running the

dapr init -kcommand, make sure that you have the correct context set in kubectl.

As an aside, if you are deploying Dapr into an Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) cluster, then there is another way. There is cluster extension (currently in preview) which can be installed using the Azure CLI. Further details are available through the Azure Docs.

The dapr-operator, dapr-placement, dapr-sidecar-injector and dapr-sentry Kubernetes services are created. These are the control plane components that enable Dapr to work in your Kubernetes environment.

- dapr-operator: I’d consider this as the brain behind Dapr. It manages updates to components (state store, bindings, etc.), as well as the Kubernetes service endpoints that enable these.

- dapr-sidecar-injector: Injects Dapr into any pods that have the appropriate annotation. Parameters can be passed in to ensure the appropriate Dapr environment variables are configured (similar to you passing flags when using

dapr runin the local environment). - dapr-placement: Only needed if actors are used in your deployment. This service maps the actor instances of your applications to Kubernetes pods.

- dapr-sentry: Acts as a certificate authority, enabling mTLS between your deployed microservices.

Once you have the control plane in place, you can begin deploying your workload by using Kubernetes manifests as you usually would. To leverage the Dapr building blocks, you’ll also need to deploy any required Dapr component configurations (which can also be achieved using yaml files and kubectl apply).

I’ll cover this in more detail in a separate blog post. I’ll also post another writeup on using DAPR (and KEDA) in Azure Container Apps.

Note: If you’re intrigued and plan to get the control plane configured, there are some production guidelines available on the Dapr docs as well.

What is the state of Dapr at time of writing?

The Dapr team made a promise in their announcement blog post that they planned to bring Dapr to a vendor-neutral foundation to enable open governance and collaboration. In early 2021, the Dapr team began to follow-up on that promise and proposed to donate Dapr to the Cloud Native Compute Foundation (CNCF) as an incubation project. It was accepted as an incubation project in November 2021, and is still in that state at time of writing.

If you’re unfamiliar with the Cloud Native Compute Foundation (CNCF) or the lifecycle/stages of the project that they host, then take a look at my blog post Introducing the Cloud Native Compute Foundation (CNCF) as well as the episode with Annie Talvasto on Top new CNCF projects to look out for.

Summary

That’s a whistle-stop introduction to The Distributed Application Runtime (Dapr). It shows a lot of promise in solving several of the common challenges associated with Microservices. In the next post, we’ll explore Dapr more hands-on with a sample application that uses example components.

Have you already tried Dapr? Or, is this your first time reading about it? What are your thoughts? Please let me know in the comments!

Related

Inspired by the recent episode with Annie Talvasto, I wanted to put together a blog post that will introduce an ongoing series on Cloud With Chris. Before we introduce that series though, it’s important that we first introduce the Cloud Native Compute Foundation (more commonly known as CNCF).

Blog

In part 1 of this Using Azure Arc for Apps series, we explored Azure Arc and Azure Arc enabled Kubernetes clusters. In this post, we’ll be exploring Event Grid for Kubernetes. At time of writing, this approach is in public preview, so we may see certain limitations / features that are not yet available.

Blog